Quasars - Facts for Kids

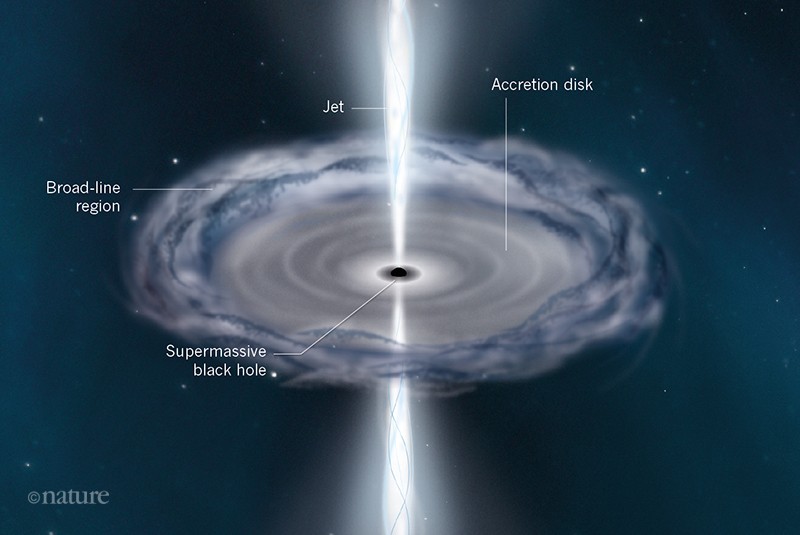

Quasar 3C 273, an astronomical object with a supermassive black hole surrounded by hot gas and dust that's pulled towards the black hole. [Credit: Nature]

If you click on a link, press the back arrow on your browser to come back to the story.

Quasars are the most brilliant objects in the universe.

We can feel the Sun's heat from 150 million kilometers (93 million miles) away. But a red supergiant like Betelgeuse gives out 40,000 times more energy than the Sun. Some day Betelgeuse will run out of fuel and explode as a supernova. For a time it will shine as brightly as our whole Milky Way galaxy.

A quasar is much brighter than a supernova. It commonly produces a hundred times more energy than a galaxy of a hundred billion stars.

Despite their brightness, at first no one could see quasars.

In the 1950s, astronomers using radio telescopes first discovered quasars. Some quasars give off strong radio waves. Yet no one knew what they were because they couldn't match up the radio sources with anything they could see.

The first quasars that astronomers saw looked like weird stars.

Through a telescope, planets are disks, nebulae and galaxies are fuzzy, and stars look like points of light. When American astronomer Allan Sandage first saw a quasar, it was star-like, but its light spectrum was odd.

A spectrum is the pattern of colors and lines we see when light is split up. The lines for different elements are labelled on the diagram. A spectrum tells astronomers what the the star is made of and how hot it is. But Sandage saw a spectrum with lines that didn’t match any known substance.

Quasars are not only incredibly bright, but also incredibly far away.

Dutch astronomer Maarten Schmidt first connected one of the unknown radio sources (3C 273) to one of the weird star-like objects we now call quasars. He realized that the strange lines in the spectrum were hydrogen, but that they were redshifted. This means that the lines had moved closer to the red end of the spectrum because the object was moving away from us.

You can see redshifted lines in this diagram. The bottom spectrum shows what the spectral lines look like in the lab. The others show how they're shifted for objects in space. The amount of the shift tells us how fast an object is moving. [Image credit: © Copyright 2012, via Space Exploratorium.]

Once you know an object's velocity, you can work out how far away it is. Schmidt was amazed to find that 3C 273 was two and a half billion light years away. It’s our closest quasar, but we know of over 200,000 of them. The farthest one is 13 billion light years away.

The big question was: What is out there that’s so bright we can see it from billions of light years away?

The big answer is: a supermassive black hole in the heart of a galaxy. A region about the size of the Solar System is responsible for all the activity, drowning out the light of the rest of the galaxy.

A supermassive black hole has the mass of a million suns or more, and it’s surrounded by a disk of material that it's pulling in. The material swirls round and round at high speed before falling into the black hole. This produces enormous amounts of radiation that we can detect, even though we can’t see the black hole itself.

A telescope is a time machine and quasars are clues to the past.

Light travels at 300,000 kilometers (186,000 miles) per second. That’s fast, but it’s a big universe. We can’t see anything until its light gets to us. So the light from a quasar five billion light years away took five billion years to get here. Since Earth is 4.6 billion years old, we see the quasar as it was before Earth even existed. There aren't any quasars closer than 2.5 billion light years even though they're common farther away.

There are quasar-like objects and black holes in local galaxies.

Although there aren't any nearby quasars, there are many objects similar to quasars that are closer to us than 2.5 billion light years. We call them Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN). Like quasars, they're powered by supermassive black holes. They lie in the center of a galaxy and outshine the galaxy, but aren't as bright as quasars.

In fact, it's likely that most galaxies contain a supermassive black hole. The Milky Way has one with a mass of four million Suns, but there isn’t enough fuel for it to be active. Black holes can only pull in matter that's nearby. Probably quasars became weaker as the nearby matter got scarcer, and most of them quieted down leave less spectacular black holes.

If you click on a link, press the back arrow on your browser to come back to the story.

Quasars are the most brilliant objects in the universe.

We can feel the Sun's heat from 150 million kilometers (93 million miles) away. But a red supergiant like Betelgeuse gives out 40,000 times more energy than the Sun. Some day Betelgeuse will run out of fuel and explode as a supernova. For a time it will shine as brightly as our whole Milky Way galaxy.

A quasar is much brighter than a supernova. It commonly produces a hundred times more energy than a galaxy of a hundred billion stars.

Despite their brightness, at first no one could see quasars.

In the 1950s, astronomers using radio telescopes first discovered quasars. Some quasars give off strong radio waves. Yet no one knew what they were because they couldn't match up the radio sources with anything they could see.

The first quasars that astronomers saw looked like weird stars.

Through a telescope, planets are disks, nebulae and galaxies are fuzzy, and stars look like points of light. When American astronomer Allan Sandage first saw a quasar, it was star-like, but its light spectrum was odd.

A spectrum is the pattern of colors and lines we see when light is split up. The lines for different elements are labelled on the diagram. A spectrum tells astronomers what the the star is made of and how hot it is. But Sandage saw a spectrum with lines that didn’t match any known substance.

Quasars are not only incredibly bright, but also incredibly far away.

Dutch astronomer Maarten Schmidt first connected one of the unknown radio sources (3C 273) to one of the weird star-like objects we now call quasars. He realized that the strange lines in the spectrum were hydrogen, but that they were redshifted. This means that the lines had moved closer to the red end of the spectrum because the object was moving away from us.

You can see redshifted lines in this diagram. The bottom spectrum shows what the spectral lines look like in the lab. The others show how they're shifted for objects in space. The amount of the shift tells us how fast an object is moving. [Image credit: © Copyright 2012, via Space Exploratorium.]

Once you know an object's velocity, you can work out how far away it is. Schmidt was amazed to find that 3C 273 was two and a half billion light years away. It’s our closest quasar, but we know of over 200,000 of them. The farthest one is 13 billion light years away.

The big question was: What is out there that’s so bright we can see it from billions of light years away?

The big answer is: a supermassive black hole in the heart of a galaxy. A region about the size of the Solar System is responsible for all the activity, drowning out the light of the rest of the galaxy.

A supermassive black hole has the mass of a million suns or more, and it’s surrounded by a disk of material that it's pulling in. The material swirls round and round at high speed before falling into the black hole. This produces enormous amounts of radiation that we can detect, even though we can’t see the black hole itself.

A telescope is a time machine and quasars are clues to the past.

Light travels at 300,000 kilometers (186,000 miles) per second. That’s fast, but it’s a big universe. We can’t see anything until its light gets to us. So the light from a quasar five billion light years away took five billion years to get here. Since Earth is 4.6 billion years old, we see the quasar as it was before Earth even existed. There aren't any quasars closer than 2.5 billion light years even though they're common farther away.

There are quasar-like objects and black holes in local galaxies.

Although there aren't any nearby quasars, there are many objects similar to quasars that are closer to us than 2.5 billion light years. We call them Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN). Like quasars, they're powered by supermassive black holes. They lie in the center of a galaxy and outshine the galaxy, but aren't as bright as quasars.

In fact, it's likely that most galaxies contain a supermassive black hole. The Milky Way has one with a mass of four million Suns, but there isn’t enough fuel for it to be active. Black holes can only pull in matter that's nearby. Probably quasars became weaker as the nearby matter got scarcer, and most of them quieted down leave less spectacular black holes.

You Should Also Read:

Life and Death of Massive Stars – Facts for Kids

Stellar Misunderstandings

Icarus at the Edge of Time book review

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Mona Evans. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Mona Evans. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mona Evans for details.